Internal street of Savda Ghevra, a resettlement colony on the west periphery of Delhi, developed in the third wave.

What is a Resettlement colony ?

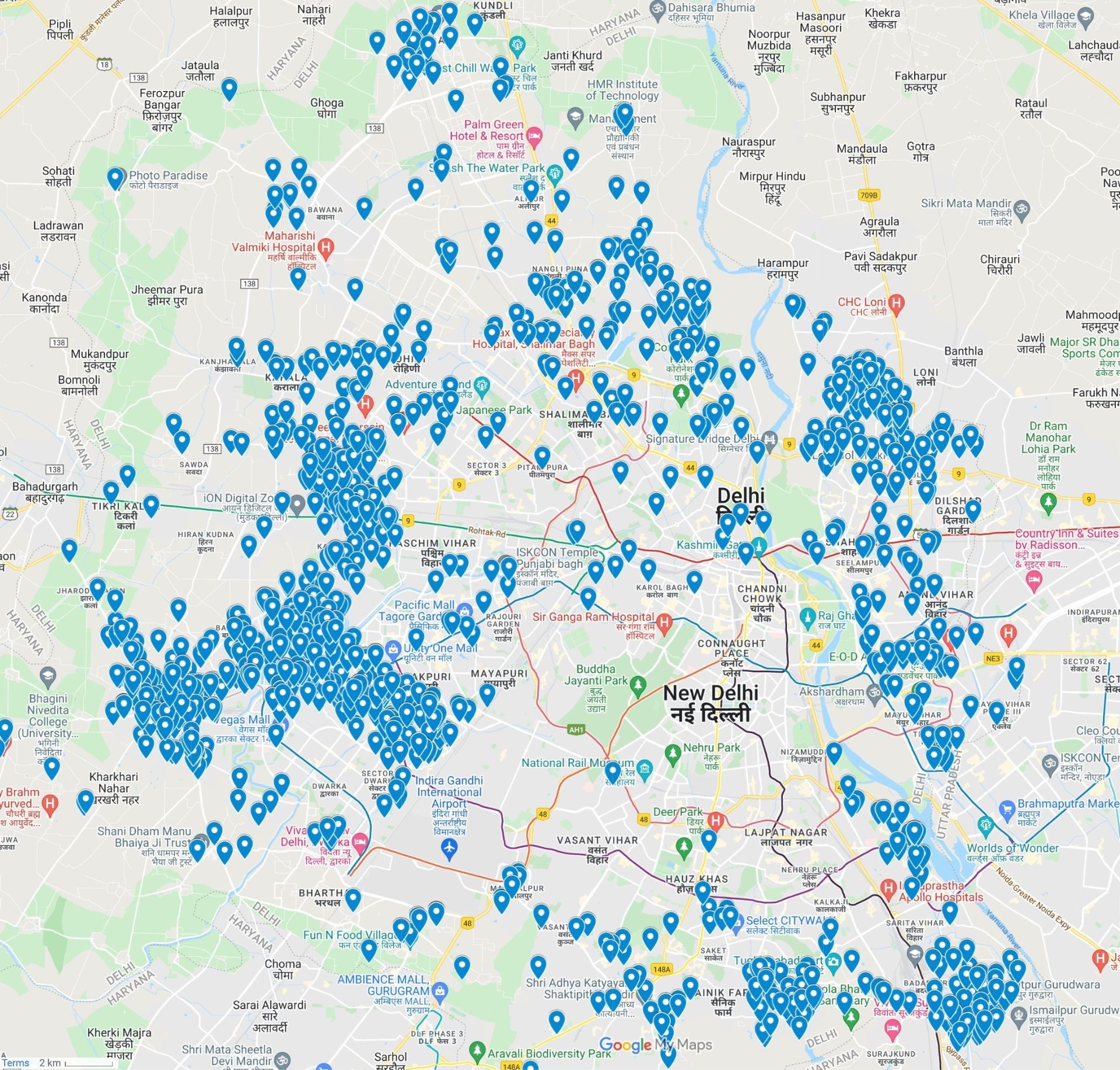

Resettlement colonies are state-allotted plots/homes to households resettled mostly from Jhuggi Jhopri Clusters (JJCs). Residents are given tenurial rights based on the respective state’s applicable policy at that time. Although resettlement colonies are the closest to formal planned colonies (in a way that they are included within the development area of the master plan, and are zoned as residential, while following specific standards and norms), most of these suffer from a lack of quality basic infrastructure services such as piped water, drainage, etc. Currently, over 17.76 lakh people reside in Delhi’s resettlement colonies, which is around 12.7% of the city’s population.

History

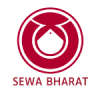

In Delhi, resettlement has taken place broadly in three phases. The first and second took place between the 1960s and ‘70s creating over 44 colonies across Delhi. The third phase was a response to the upcoming commonwealth games in Delhi and took place between 2006 and 2008 accommodating a large population across 11 colonies. Through these phases, parameters such as eligibility criteria, documentation requirements, size of plots, associated costs, nature of tenure security, and cut-off dates have seen change. The plot size in the 1960s was 80 sq yards i.e. 66.9 sq m which was reduced to 20.9 sq m in 1976 and further reduced to 18 and 12.5 sq m in the third phase.

Click here to look at Delhi’s Resettlement Colonies

Source: Housing and Land rights Network

Policy Barriers

DELHI MASTER PLAN 2041

- Singular Development Approach: The 2041 Master Plan acknowledges that resettlement colonies are facing ‘issues of accessibility, lack of adequate services, and poor quality of construction and dilapidation’. However, it offers a singular development approach to these issues via regeneration. This process is time, cost and resource intensive, and does not consider the built form, as well as other diverse requirements of residents. The plan should prioritise and insist on basic service provisioning and the upgradation of the neighbourhood without linking this to regeneration.

- Lacking Provisions for Consent and Secure Tenure: That apart, while provisions for regeneration are detailed, the plan omits details about minimum residents’ consent in the process. The plan also fails to make provisions for secure tenure, without which entering into regeneration or plot amalgamation will raise further complications.

Phase III: 2006 JJ RESETTLEMENT

- Expired license and no clarity on tenure security: Despite state resettlement in 2006, colonies established in this phase were offered a short-term 10-year license. This license expired in 2016 leaving residents in precarity and without legal protection that would prevent further displacement or eviction. Despite a push from CSOs, there has been no notification extending the license or offering permanent solutions. As detailed below, the freehold conversion policy also fails to make provisions for the colonies established in the 3rd phase.

- Restrictions on use and mortgage: Apart from the insecure tenure granted to residents, restrictions have also been placed on mortgage, renting, and transfer.

- Inadequate Service Provisioning: The 2006 phase of resettlement was largely peripheral to areas that had seen no provisioning for bulk infrastructure in the form of sewerage, or water pipelines. Considering this peripherality, there was also no attempt to create livelihood opportunities, or provide adequate and accessible transportation facilities.

Phase I and II: 1960s and 1970s – FREEHOLD CONVERSION POLICY DEFICIENCIES

- Progressively expensive: Conversion rates are calculated based on the circle rate which is market-dependent. In informal settlements, mixed-use is prevalent, and such commercialisation makes conversion costlier. Further, most buildings were built incrementally up to two or three floors, and the conversion rate accounts for the number of floors as well. As noted earlier, the conversion rate also increases if ownership has seen a change. These aspects make freehold conversion costly and impossible for the residents to afford. For example: In Raghubir Nagar, for a plot size of 20.9 sq m, the scheme costs Rs. 2,41,395/- at 30% of the circle rate and Rs 8,04,650 /- at 100%. (Note: These rates as calculated by DUSIB and based on the circle rate notified in the year 2012).

- Difficult documentation requirements: Apart from basic documentation (Aadhar, Voter ID Card etc), the policy requires submission of ‘succession certificates’, showing inheritance and transfer. In many cases, the original allottee is no longer alive and the inheritance of the property has not been documented. Accessing the certificate requires legislative processes which are both time and cost-intensive.

- Lack of clarity in the process: The policy lacks a clear pathway that lays out the procedure at every step. There is also no procedural clarity on renewing documentation if any property document is displaced / lost. For example, many residents have misplaced the allotment slip (a mandatory document in the policy) and the formal procedure for its renewal is not clear.

- No recognition of ground realities: The colonies are more than 50 years old and several extensions and amalgamations of buildings have taken place to accommodate families. The buildings’ bye-laws, however, are measured against the original regulations, categorising the changes as unauthorised. Residents are often questioned and threatened, discouraging engagement with government officials and schemes.

Ways forward

DELHI MASTER PLAN 2041

- Services and regeneration to be delinked: The 2041 Master plan should not see regeneration as the only pathway to improving service provisioning. Most residents have built homes incrementally with heavy monetary investments. The state should acknowledge this and prioritise retrofitting and upgradation of services over regeneration.

- Participatory approach: Regeneration is a cost and time-intensive exercise, and thus needs to be an inclusive process involving the community, RWAs and NGOs. A minimum of 50% consent from the residents should be mandated.

2006 RESETTLEMENT

- Prioritise service provisioning: Resettlement is a state-provided formal housing facility, and should thus be seen in comparison with planned housing. Service provisioning in these colonies should be at par with planned colonies and be provided on priority.

- Strengthened tenure: Without an extension and clarity on tenure, residents are unlikely to opt for the formalisation of plot amalgamation or regeneration. The plan needs to issue guidelines that strengthen tenure security either through affordable freehold conversion or via a long-term license

FOR FREEHOLD CONVERSION POLICY

- Policy affordability: A major barrier to conversion is its exorbitant cost. The policy should be made affordable and it should recognise that change in ownership is a given considering over 50 years have passed. The policy should set a flat rate, and not base costs on circle rates. Payment options in tranches should be offered as well.

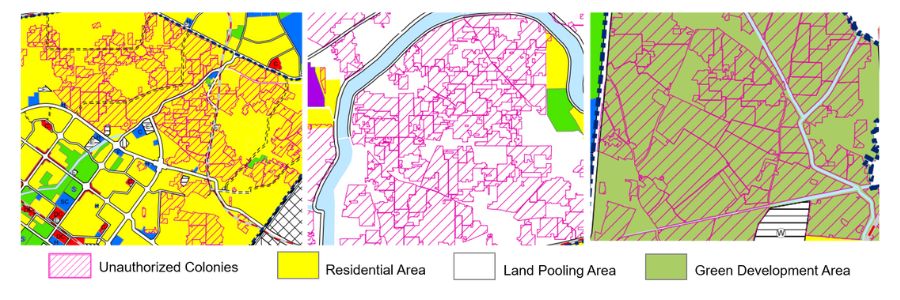

Establishment of a dedicated wing / office: A dedicated wing should be formed under DUSIB that purely deals with freehold conversion processes, such as the PM-UDAY cell formed under DDA that handles matters related to the authorisation of properties in unauthorised colonies. The dedicated wing will allow the department to lay a clear pathway and address issues at every level. - Recognise extensions and amalgamations: The policy needs to recognise ground-level changes such as extensions and amalgamations, and not penalise residents that apply for the scheme.

- Make the documentation process easier: Most property documents required under the current policy are non-existent with the residents, and their procurement is complicated. The policy should simplify the process, and via a dedicated wing, fast-track the requirements of residents and facilitate the creation of required documentation.

- Extend scheme to other colonies: The resettlement colonies formed in the last phase have not been included in the freehold scheme. Other arrangements for the extension of their tenure have also not been formulated. The scheme should include these colonies so that they too can benefit from conversion to freehold and extend the use of their properties to selling, rent and mortgage.

Disclaimer : The content of this webpage is based solely on research and on-ground implementation work during the ZAA (Zamini Adhikaari Abiyaan) project under the WOW (Work and Opportunities for Women) vertical, funded by the FCDO (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) and implemented jointly with the Mahila Housing Trust (MHT). At present, the roadmap aims to visually depict the de-facto and de-jure strategies that aid in accessing tenure security for three types of informal settlements in Delhi – Unauthorised colonies, resettlement colonies, and slums. It is an attempt to collate the opportunities and barriers encountered by SEWA to access tenure security in the informal settlements of Delhi and is intended to be used by researchers, academicians, students, and civil society organisations (CSOs).

50% of the area under UACs is demarcated for

50% of the area under UACs is demarcated for